Plot Synopsis (continued)

After

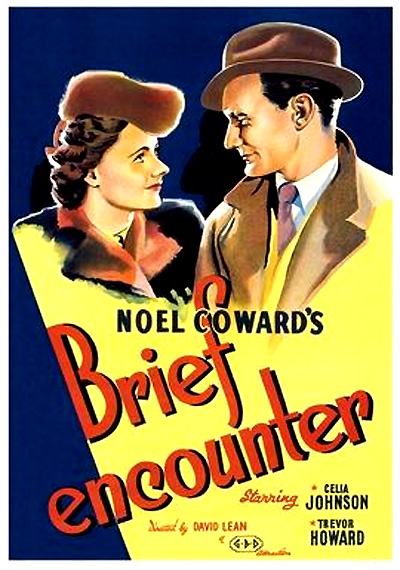

lunch, they innocently attend the cinema together, choosing to see "Love

in the Mist" at the Palladium. [Laura insists that they each

pay their own separate admission but Alec buys them tickets for the

upstairs balcony anyway. The trailer/preview before the main feature

is for a film titled "Flames of Passion" - advertised as: "Stupendous," "Colossal," "Gigantic," and "Epoch-Making." After

lunch, they innocently attend the cinema together, choosing to see "Love

in the Mist" at the Palladium. [Laura insists that they each

pay their own separate admission but Alec buys them tickets for the

upstairs balcony anyway. The trailer/preview before the main feature

is for a film titled "Flames of Passion" - advertised as: "Stupendous," "Colossal," "Gigantic," and "Epoch-Making."

Laura: I feel awfully grand perched up here. It was

very extravagant of you.

Alec: It was a famous victory.

Laura: Do you feel guilty at all? I do.

Alec: Guilty?

Laura: You ought to more than me, really. You neglected your work

this afternoon.

Alec: I worked this morning. A little relaxation never did harm to

anyone. Why should I always feel guilty?

Laura: I don't know.

Alec: How awfully nice you are!

The movie theatre's organ ascends from underneath the

floor, causing Laura to exclaim: "It can't be!" They share

a laugh together.

We walked back to the station together. Just as we

reached the gates, he put his hand under my arm. I didn't notice

it then, but I remember it now.

Laura: What's she like, your wife?

Alec: Madeleine? Small, dark, rather delicate.

Laura: How funny! I supposed she would have been fair.

Alec: And your husband. What's he like?

Laura: Medium height. Brown hair. Kindly, unemotional, and not delicate

at all.

Alec: You said that proudly.

Laura: Did I?

They share a cup of tea and fresh Banbury buns at a

corner table in the railway station's refreshment room before their

trains depart in opposite directions. He admits to being a social

idealist - combined with boyish, youthful enthusiasm for his occupation

in preventive medicine. Slowly and imperceptibly behind their very

understated British restraint and formality, the couple finds their

lives are transformed by their mutual attraction, with intense moments

of great tenderness, gentleness, and loving care:

Laura: Why did you become a doctor?

Alec: That's a long story. Perhaps because I'm a bit of an idealist.

Laura: I think all doctors ought to have ideals, really. Otherwise,

their work would be unbearable.

Alec: Surely, you're not encouraging me to talk shop.

Laura: Why shouldn't you talk shop? It's what interests you most,

isn't it?

Alec: Yes, it is. I'm terribly ambitious really, not ambitious for

myself so much as for my special pigeon.

Laura: What is your special pigeon?

Alec: Preventive medicine.

Laura: I see.

Alec: I'm afraid you don't.

Laura: I was trying to be intelligent.

Alec: Most good doctors, especially when they're young, have private

dreams. That's the best part of it. Sometimes though, those get over-professionalized

and strangulated...What I mean is this, all good doctors must primarily

be enthusiasts. They must, like writers and painters and priests,

they must have a sense of vocation. A deep-rooted, unsentimental

desire to do good.

Laura: Yes, I see that.

Alec: Well, obviously one way of preventing disease is worth fifty

ways of curing it. That's where my ideal comes in. Preventive medicine

isn't anything to do with medicine at all, really. It's concerned

with conditions, living conditions and hygeine and common-sense.

For instance, my specialty is pneumoconiosis...it's nothing

but a slow process of fibrosis of the lung due to the inhalation

of particles of dust. In the hospital here, there are splendid opportunities

for observing cures and making notes because of the coal mines.

Laura: You suddenly look much younger.

Alec: Do I?

Laura: Almost like a little boy.

Alec: What made you say that?

Laura (as the lyrical Rachmaninoff's Piano Concerto plays

in the background): I don't know. Yes I do.

Alec: Tell me.

Laura: No, I couldn't really. You were saying about the coal mines.

Alec: Oh yes. The inhalation of coal dust...

They look intently into each other's eyes and the music

builds, as Alec recites various forms of lung disease and his idealistic

dedication to his medical profession. Their conversation comes to

an end when Alec's train bell sounds. Hastily, Alec initiates further

meetings ("Shall I see you again?"). They make plans to

continue seeing other, not by chance any more but in planned meetings

during Thursday rendezvous that eventually become less and less innocent:

Laura: It's been so very nice. I've enjoyed my afternoon

enormously.

Alec: I'm so glad. So have I. I apologize for boring you with long

medical words.

Laura: I feel dull and stupid not to be able to understand more.

Alec: Shall I see you again?

Laura (not answering his question): It's out on the platform, isn't

it? You have to run. Don't bother about me. Mine's not due for a

few minutes.

Alec: Can I see you again?

Laura: Yes, of course. Perhaps you'll come out to Ketchworth one

Sunday. It's rather far, but we should be delighted...

Alec: Please, please.

Laura: What is it?

Alec: Next Thursday, the same time.

Laura: No, I couldn't possibly.

Alec: Please. I ask you most humbly.

Laura: You'll miss your train.

Alec: All right.

Laura: Run.

Alec (extending his hand): Goodbye.

Laura: I'll be there.

Alec: Thank you, my dear.

Following their third meeting together (after meeting

a month earlier), they cheerfully wave to each other as Alec's train

departs. Laura ponders every action Alec may make as he returns home

- but then a wave of doubt sweeps over her as she struggles with

her romantic yearnings:

I stood there and watched his train draw out of the

station. I stared after it, until its tail light had vanished into

the darkness. I imagined him getting out at Churley, giving up

his ticket, walking back through the streets, letting himself into

his house with his latchkey. His wife Madeleine, will probably

be in the hall to meet him, or perhaps upstairs in her room, not

feeling very well. Small, dark, and rather delicate. I wondered

if he'd say: 'I met such a nice woman at the Kardomah. We had lunch

and went to the pictures.' And then suddenly, I knew that he wouldn't.

I knew beyond a shadow of doubt that he wouldn't say a word - and

at that moment, the first awful feeling of danger swept over me.

(The steam from her arriving train hisses at her.)

In the train compartment on the trip home, she guiltily

wonders about the other passengers, squirming and averting her eyes

when she senses that a clergyman across from her may perceive her

sinful blushing:

I looked hurriedly around the carriage, to see if

anyone was looking at me, as if they could read my secret thoughts.

No one was, except a clergyman in the opposite corner. I felt myself

blushing and opened my library book and pretended to read.

Tormented, she buries her frustrated longing and vows

never to see Alec again. She blames herself for neglecting her obligations

at home when she returns and finds that her child has been hurt in

an accident:

By the time I got to Ketchworth, I'd made up my mind

definitely that I wasn't going to see Alec anymore...I walked up

to the house quite briskly and cheerfully. I'd been behaving like

an idiot admittedly, but after all, no harm had been done. You

met me in the hall. Your face was strained and worried and my heart

sank.

Her young boy was knocked down by a car on his way

home from school and suffered a "slight concussion." She

hovers over his bed, terrified and imagining being punished for straying

from society's conventions and neglecting family responsibilities:

I felt so dreadful, Fred, looking at him lying there

with that bandage round his head. I tried not to show it, but I

was quite hysterical inside, as though the whole thing were my

fault, a sort of punishment, an awful sinister warning.

An hour or two later however, Bobbie felt better and "reveled

in the fact that he was the center of attraction." In front

of the domestic hearth fire while Fred stolidly works on another

crossword puzzle, they discuss options for Bobbie's future - a career

in the distant navy or in a nearby office where she can "see

him off on the 8:50 every morning." Suddenly, Laura spins around

and confesses her rendezvous with Alec, but her kindly, unquestioning

husband is more interested in his crossword puzzle than in her. He

misunderstands her worries about her new acquaintance:

Laura: I had lunch with a strange man today and he

took me to the movies.

Fred: Good for you.

Laura: He's awfully nice. He's a doctor.

Fred: A very noble profession.

Laura: Oh dear.

Fred: It was Richard the Third who said: 'My kingdom for a horse,'

wasn't it?

Laura: Yes, darling.

Fred: Yes, well I wish to goodness he hadn't, 'cause it spoils everything.

Laura: I felt perhaps we might ask him to dinner one night.

Fred: By all means. Who?

Laura: Dr. Harvey. The one I was telling you about.

Fred: Must it be dinner?

Laura: Well, you're never at home for lunch.

Fred: Exactly.

Laura: Oh Fred (laughing)...

Fred: Now what on earth's the matter?

Laura: It's nothing...oh Fred...

Fred: I really don't see what's so frightfully funny.

Laura: Oh, I do. It's, it's all right darling. I'm not laughing at

you. I'm laughing at me. I'm the one that's funny. I'm an absolute

idiot. Worrying myself about things that don't exist and making mountains

out of molehills.

Fred: I told you when you came in that it was nothing serious. There

was nothing to get into such a state about.

Laura: I do see that now, I really do (more elated laughing).

The next Thursday, a dutiful Laura rationalizes a fourth

meeting with Dr. Harvey, and then realizes how melancholy she feels

by his unexpected absence:

When Thursday came, I went to meet Alec, more as

a matter of politeness than for any other reason. It didn't seem

very important, but after all, I had promised. I managed to get

the same table, I waited a bit but he didn't come. The ladies'

orchestra was playing away as usual. I looked at the cellist. She

had seemed to be so funny last week. Today she didn't seem funny

any more. What a pathetic poor thing. After lunch, I happened to

pass by the hospital. I remember looking up at the windows and

wondering if he were there, or was there something awful that happened

to prevent him turning up. I got to the station earlier than usual.

I hadn't enjoyed the pictures much. It was one of those noisy musical

things that I'm so sick of them. I'd come out before it was over.

As I took my tea to the table, I suddenly wondered if I'd made

a mistake - that he'd meant me to meet him there.

At the train station, Laura is amused while watching

the banterings and adolescent flirtations of the British working-class

relationship between the hostess and the station guard. The 5:40

bell rings to warn of her approaching train, and she is worried and

desperate that Alec is failing to show:

As I left the refreshment room, I saw a train coming

in, his train. He wasn't on the platform, and I suddenly felt panic-stricken

at the thought of not seeing him again.

Suddenly, Alec races toward the station, as frantic to

see her as she is to see him - the poignancy of the moment is loudly

underscored by Rachmaninoff's concerto, drowning out his explanation

for being late. It is at this juncture that they both realize they have

fallen in love. She rushes with him under the tracks to the door of his

departing train, her face beaming:

Alec: I'm so glad I had a chance to explain. I didn't

think I'd see you again.

Laura: Enough said, now go quickly, quickly.

Alec (on board the moving train): Next Thursday?

Laura: Yes, next Thursday.

Alec: Goodbye.

Laura: Goodbye.

Alec: Thursday. Goodbye.

For their fifth meeting (in six weeks) on a Thursday,

they first attend the Milford Cinema and sit in the balcony a second

time. They view a humorous cartoon of loveable Donald Duck, exhibiting "his

dreadful energy and his blind frustrated rages." When the main

picture "Flames of Passion" begins (a film fantasy that

will work its magic upon them - especially upon Laura who lives a

life of romantic fantasy), Alec warns of the fresh stimulation of

their emotions which will result:

It's the big picture now. Here we go. No more laughter.

Prepare for tears.

[Screen credits reveal that the fictitious film is "Based

on the Novel 'Gentle Summer' by Alice Porter Stoughey." In parallel

fashion, Laura's imagination is highly-charged and passionate, while

the reality of her brief encounter is more commonplace and low-key.]

They leave the theatre, stand outside, and then decide to go to the

park - an invigorating interlude in a naturalistic, but drab setting

(the first time they break away from their emotionally-constrained,

stunted environment). In the Botanical Gardens, where boys sail boats

on the lake and white swans swim on the water's surface, they rent

a boat for the day, even though the boats are "covered up":

It was a terribly bad picture. We crept out before

the end, rather furtively, as though we were committing a crime.

The usherette at the door looked at us with stony contempt. It

was a lovely afternoon. It was a relief to be in the fresh air.

We decided we'd go to the Botanical Gardens. Do you know, I believe

we should all behave quite differently if we lived in a warm, sunny

climate all the time? We shouldn't be so withdrawn and shy and

difficult. Oh Fred, it really was a lovely afternoon. There were

some little boys sailing their boats - one of them looked awfully

like Bobbie. That should have given me a pang of conscience I know,

but it didn't. I was enjoying myself, enjoying every single minute.

Alec suddenly said that he was sick of staring at the water and

that he wanted to be on it. All the boats were covered up, but

we managed to persuade the old man to let us have one. He thought

we were raving mad. Perhaps he was right. Alec rowed off at a great

rate, and I trailed my hand in the water. It was very cold but

a lovely feeling...

Alec admits his lack of rowing experience and advises

that she steer their directionless rowboat: "And unless you

want to go round and round in ever-narrowing circles, you'd better

start steering." They let the flow of the water take them along

its course, until they figuratively and physically bump into a man-made

barrier under a stone bridge (a symbol of the narrow obstacles in

their repressive environments and private lives). |